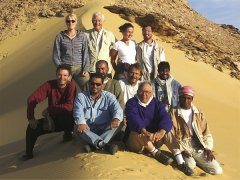

Click on image for list of participants

|

Jebel Uweinat - Gilf Kebir Expedition

20th October - 5th November, 2002

NOTICE: The rock art photos on this page are strictly copyrighted ! No photo may be copied / used for any purpose without written permission.

|

Day 1. - Cairo - Dakhla.

With an early morning start from Cairo we were in Dakhla by seven in the evening afrer a dull, uneventful day. We picked up our escorting officer, Colonel Ashraf at Baharya (much to our surprise, he turned out to be the commanding officer of the Baharya border guards unit, which speeded our progress at various checkpoints tremendously), and by ten in the evening we have fuelled the two cars, had all the supplies, and were ready to set out next dawn.

Day 2. - Dakhla - Dunes on Selima Sand Sheet.

The morning was spent with the boring 300 kilometre drive down south on the tarmac road along the Darb el Terfawi. With only two cars, the load was very heavy, so we had to drive at a snail pace to protect the tyres and suspension. We looked with some anxiety at the perfectly flat rear springs of the second car (carrying all our water and most of our supplies in addition to it's 600 litre fuel load), but the Toyotas proved themselves again - we did not even have a single flat tyre along the whole 2000 kilometre trip. Turn off point was about 30 kilometres before Bir Terfawi, where the low sandstone ridges give way to the perfectly flat Selima Sand Sheet. We had a brief lunch stop at the Abu Hussein Dunes, then continued for another 120 kilometres to make camp at the next dune range, at 27o 30' East.

Day 3. - Accross the Selima Sand Sheet to Karkur Talh.

Next day we quickly crossed the remainder of the Selima Sand Sheet, rounded the southern corner of the Gilf, and continued along the flat plain towards Clayton's Craters. Incredibly, the biggest terrain obstacle along our route were the deep ruts made by the Kufra Supply Convoys more than sixty years ago. The sand is still soft, and with the heavy cars we could not risk a broken spring due to hitting a ditch at high speed. It took almost an hour to get accross the three kilometre wide valley, filled with old tracks. Still, by mid afternoon we reached Crater D in time for lunch and a brief reconnaissance. In another hour and a half we cleared the entrance of Karkur Talh, and made our camp in a little side valley of the main southern branch about 10 kilometres inside.

Day 4. - Karkur Talh.

The Southern branch was explored by both Almásy / Rhotert and Winkler, and a number of rock art sites were found, however my feeling was that much of the lesser side wadis were unexplored. As the Belgian team did not even visit this area in 1968 (or at least took no photos), there was a good chance that a thorough exploration may reveal new sites. As we set out, we immediately began to find engravings close to the main valley, one reported by Winkler, but the majority unknown.

Further up the previously unexplored side valleys, we have found numerous shelters containing paintings of varying quality.

Near a dry waterfall, a shelter contained a remarkable set of paintings, unmistakably in the classical 'roundhead' syle. While later we have found better preserved, larger sites, certainly this shelter is the most significant discovery of the trip!

The results of the first day of exploration surpassed all expectations: we have found a total of 25 new sites, 15 engravings, and 10 paintings.

Day 5. - Day trip to Karkur Murr

We set out along almost the same route that we have taken with Wolfgang and Salama two years ago. This time we did not follow the footpath, but took the bed of the little side wadi leading south to Winkler's Site 81. Near the beginning of the wadi, we found a few smaller paintings, plus the large shelter that was discovered by Jean-Marc Mercier and their party earlier this year.

After visiting Site 81 and the other shelters near-by, we continued up the valley towards the watershed, and soon descended into one of the upper branches of karkur Murr.

Immediately we found a shelter with paintings, and another one further down the valley, just beyond the point where we turned back last time.

As we progressed, the meagre vegetation along the bottom of the valley began to turn markedly green. After a bend, we were confronted with an unexpected sight, a date palm growing in the wadi bed. Water must be near ! Sure enough, after the next bend, at the foot of a large rectangular block, there was the little pool in a small rock basin, thickly grown with grass, Ain el Brins. The water tasted bitter, was full of floating dead plant remains, but was drinkable. A little further downstream, there was a littre real oasis, a dense cluster of palms blocking the middle of the valley. All about, there were plenty of signs of past human habitation from the Tibou times, but no sign of any recent visitors. On the rock above the spring, we found the 1934 inscription of the now familiar No 1 Motor Machine Gun Battery of the Sudan Defence Force.

I had brought home a one litre sample from the spring, that was analysed by the laboratory of the Hydrological Research Institute in Budapest. Despite the bitter taste, the salts content is surprisingly low. Except for the slightly higher than permissible sulphate and high manganese contens, and the alkaline pH, after filtering out all the dead plant matter it would pass the drinking water standards:

| pH |

|

5.9 |

| Specific conductivity |

µS/cm |

480 |

| Chemical oxygen absorbtion |

mgO2/l |

1.35 |

| Ammonium |

NH4mg/l |

0.41 |

| Nitrites |

mg/l |

<0.01 |

| Nitrates |

mg/l |

<1 |

| Chlorides |

mg/l |

31 |

| Sulphates |

mg/l |

210 |

| Alkalinity |

mmol/l |

0.8 |

| Total hardness |

CaOmg/l |

110 |

| Calcium |

mg/l |

45 |

| Magnesium |

mg/l |

23 |

| Sodium |

mg/l |

51 |

| Potassium |

mg/l |

5.0 |

| Iron |

mg/l |

0.03 |

| Manganese |

mg/l |

1.57 |

| Total dissolved matter |

mg/l |

472 |

In the afternoon we spent several hours exploring the side wadis in search of Winkler's elusive Site 75, without luck. The location of this site is a mystery, as with the trip two years ago, now practically all the western side wadis fitting Winkler's description have been thoroughly surveyed...

On our return journey, we made directly for camp accross a five kilometre stretch of almost flat, gravely plain separating Karkur Murr from the southern branch of Karkur Talh.

Day 6. - Karkur Talh

In the morning a few leisurely hours were spent looking for a few sites recorded by Rhotert, Almásy, Winkler and Jean-Marc Mercier in the main valley, which we missed on previous trips. They were all found easily, mostly in conspicious places, making us wonder how many unrecorded sites have we wondered by without ever noticing?

We continued with the exploration of a side wadi, where a faint painting and some engravings were photographed (but not published) by Winkler. Much to our delight, the paintings that were barely discernible on Winklers photo at the EES in London turned out to be another set of 'roundhead' type figures. There were further engravings up the valley, which was apparently unexplored save for the first two sites.

By now a definite pattern began to emerge. The engravings are concentrated in the main valley, and the beginnings of the side wadis, always near ground level, with a few scattered paintings. Then there is a fairly long empty stretch, which caused the early explorers to abandon further search. Then in some valleys (but not in all, as several hours' fruitless climb proved) there is another concentration of sites near the head of the wadi, mostly paintings. This time we were lucky: in the far upper reaches, near a large rock basin that must hold water for many months after rains, there were a cluster of sites, including a large shelter with a multitude of perfectly preserved paintings, surpassed only by a handful of other sites in the area.

Day 7 - 8. - Ascent of Jebel Uweinat

The satelite photos show two possible routes to the peak of Uweinat from the north-east, following the two main branches of Karkur Talh. Based on the photos, the northern branch seems to round the lower sandstone plateau to the north of the main massif, then enter into a narrow valley between the two from the west, close to the point where we made the ascent a year ago with Bernhard. The southern branch rises to the northern cliffs somewhere midway between the two lesser northern plateaus, near the mysterious "white blob". Both routes involve a horizontal distance at least twice that of the ascent from the west, so a two day trek was planned, making the ascent along the northern route, and returning via the other wadi.

A party of six (Andreas, Bernhard, Hannah, Kit, Salama & András) left the camp at dawn, Zayed driving us to the end of the driveable section of the northern branch. We all carried six bottles (9 litres) of water for the two days, a sleeping bag and the bare minimum of food and other things. We soon passed the known areas, the rocky bed of the wadi offering increasingly difficult going. At one point, we found a promising large shelter, that contained a single, perfectly preserved 'roundhead' figure on the ceiling. Interestingly, we found no other sites for 3-4 kilometres on either side of this locality.

As the wadi turns towards the cliffs, it passes between two eroded basalt hills on the flank of the mountain in a narrow gorge, then makes a straight approach to a saddle beteen two large plateaus surrounded by towering vertical cliffs.

From the basalt hills the route looked deceptively easy, we hoped to be up on the saddle by noon. However the mountain's dimensions are misleading. The easy looking slope in fact makes a rise of almost 800 metres, and the valley is filled with car sized boulders, making the 6 kilometres a very slow and difficult climb.

At one point, as we stopped for a short rest, we noticed a large shelter, which contained several painted cattle on the ceiling. Bernhard set out to investigate a small shelter on the opposite bank, and soon shouted back for us to follow - the shelter contained a few delicately painted human figures.

Exploring the vicinity, we glimpsed a low shelter nearby. On a close look, we found the ceiling to be completely covered with paintings of the best possible quality!

We continued the climb that became steeper, and the blocks larger. As we rested in the shade of large boulders blocking the view, and during the climb our sight was locked to the ground at our feet, we hardly noticed our progress. Near the top we looked back, and the vista proved we have come a long way.

Finally, all exhausted, we reached the col by three in the afternoon. Here the valley turned south, rounding the western cliffs, and entered a broad plain separating the cliffs from the granite hills further west. Even on this high plateau, Salama spotted a little shelter that contained a few faint painted goats.

After an hours' rest, we pushed on, to make the most of the still remaining daylight. The valley turned back towards the east, and entered a narrow dark valley between the cliffs.

After an hours' climb, just as the sun set, we reached a little sand filled amphitheatre at an altitude of 1400 metres, all surrounded by 400 metre high vertical cliffs. It was the perfect camping spot.

At this altitude the night was cold as anticipated, but not uncomfortably so (5-6 oC before dawn). After a hasty breakfast we pushed on for the final 500 metre assault. The wadi made a turn, and entered another terrace, some fifty metre higher. Under a mushroom shaped rock, to our amazement, we found some faint paintings of humans, cattle and goats.

Further up, at the base of the cliffs, in a long shelter, we discovered possibly the most beautiful painting in the whole region: an embracing couple, surrounded by a multitude of other figures and cattle. At an altitude of 1500 metres this is the highest known site, and implies a complete rethinking of the distribution of rock art sites in the area. Apparently the mountain has many more secrets yet to reveal.

Above the shelters the climb became rather difficult. The deeply eroded cliffs form stone pillars with deep ravines between them, and ascending a passable way could well mean having to descend again on the other side. It took over two hours to pass this maze of rocks, and finally have a clear way along the side of the wadi to the top of the main massif.

From a certain vantage point, we had the opportunity to peek into the strange circular "white blob" conspicious on all satelite photos. It seems to be a sand filled basin, surrounded on three sides by vertical cliffs that rise to make a wall-like perimeter. We were too far to see clearly, but it could be the remnants of an impact crater - what other force could erode a deep circular basin into the otherwise flat plateau, with the walls resisting erosion ? It will take another trip to investigate...

The wadi itself continued right up to the little basin that is under the rise capped with Bagnold's cairn. This explains the richness of the vegetation at Karkur Talh in comparison with the western valleys. Karkur Talh drains practically all of the high plateaux that form the summit of the mountain, where rain is the most likely, and carries the runoff far down to the broad valleys below. Incredibly, we found some vegetation right under the summit - a single Maerua crassifolia shrub amongst some bright green unidentified shrubs, that showed the clear signs of grazing, probably by waddan.

We reached the summit little after 9 am, and enjoyed the view from the top of the world. It was hazy, but still we could see 50-60 kilometres in all directions. In Bagnold's Cairn, we deposited the facsimile of the documents found a year earlier, as well as a note recording our visit.

Last year we noted, that Bagnold's cairn was not on the true summit, as the undulating plateau gave a false perspective. What looked like the highest point was in fact about 20 metres lower than a less conspicious rise about 2 kilometres to the west, just straddling 25o East. As it was 1934 metres, we presumed this was the 'Cima Italia' so named by the 1933 Marchesi expedition, the true peak. However this was at odds with the photo in di Caporiacco's book, which clearly showes Bagnold's cairn, with the group standing around it. (The cairn is a little below the highest ground, at a vantage point to make it clearly visible from the plain to the south). This time taking a closer look, there was a clear artificial pile of stones on the rise that we did not note a year ago, some 50 metres from the cairn. Inside, we found an empty champagne bottle, it's neck broken. After a careful look, deep inside the pile, we found the rolled note that was originally in the bottle. It was very fragile, covered with dust, clearly we could not attempt to read it there. It was carefully placed back into the bottle, being the safest container until it can be unrolled and examined.

We started our descent on the far side of the wadi, towards the suspected col where we could make our way to the northern cliffs, and find a way down to the southern branch of Karkur Talh below. This proved to be a bad mistake, and a good lesson not to rely on satelite photos alone for uncharted territory. At first the descent was fast and easy, but after an hour we reached a maze of rocks, and soon realized that all ways ahead ended in a sheer 300 metre drop into a deep valley where we expected to cross over to the lower plateau top to the north. What looked like a low col between the two plateaus was in fact a gorge over 500 metres deep. In order to continue, we had no alternative but to make our way down to the bottom, then climb again the dangerous looking slope on the far side, only to expect another steep drop on the north side of the lower plateau. After some route searching, our resident mountain goat, Salama found a barely passable way down a steep chute. With the comforting backup of two lengths of mountaineering rope that Andreas and Bernhard unexpectedly produced from their packs, we safely made it down to the bottom of the deep ravine, which we now saw to be the beginning of a large wadi that drained to the southern plains. With the jumbled rocks all about, this was completely indiscernible on the satelite image. It was already mid-afternoon, and we were no more than one quarter of the way back, with the prospect of a steep 300 metre climb in front of us, and another steep cliff behind to descend. Our water supplies were calculated to last two days with some reserve, and with another night on the mountain they would have gone dangerously low. A safer alternative was to make our way around the large eastern plateau. This way we will get close to Karkur Murr, with the known water source if needed. Thus we aimed for the eastern corner of the plateau, making our way slowly along the bouldery talus slope at the foot of the cliffs. It was very difficult going, with tired feet constantly slipping on the moving stones.

We have just rounded the south-east corner of the plateau (van Noten's Hassanein plateau) when the sun went down. We were still 6 kilometres from the car, and 4 from Ain el Brins. Fortunately we knew the terrain at the eastern foot of the cliffs from our previous walks to Karkur Murr. It is a gently undulating plateau with reasonably flat top, few deep valleys to cross. With our headlamps, we trudged along in the dusk and then the darkness, stopping frequently to rest the now very aching legs and feet. After what seemed like eternity we reached the southern tributary of Karkur Talh, and an hour later, after six hours in darkness, something glittered in the distance: the car with Zayed and Khaled fast asleep, but exactly where they were supposed to be from five in the afternoon.

Day 9. - Karkur Talh.

The day was spent in the recovery mode, dressing blisters and soothing the tortured legs. With Magdi & Raymond we took a walk to the magnificent site discovered three days before, then did some photography of known sites. During this, Salama went off to explore the high ground above the main valley, and discovered three sites at various locations. Two were close to each other, the first containing the usual bovids, but the second one was truly remarkable, with bright yellow cattle, never seen before, painted over an earlier scene of humans and bovids.

In the afternoon, with Bernhard we explored a portion of the main valley where few minor sites reported by Rhotert and Winkler were supposed to be. The valley was lovely in the low afternoon light and yes, the cows were there indeed.

In one part of the main valley we have come upon a large muslim style tomb and a smaller one beside, probably dating from the Tibou period.

To close the day we followed Salama to a site he found during the morning. Salama only said the site contains some human figures, and we were totally unprepared for the wonder that awaited us. The ceiling of a largish shelter contained perfectly executed tiny figures (some no more than 2-3 cms) in three groups, in a perfect sate of preservation. The style and composition was totally different from all other sites I know in Karkur Talh. It was certainly a fitting ending to our six days of exploration.

The final balance was impressive: 36 new engravings, and 31 new paintings in Karkur Talh (including those high up on the mountain), and two new paintings in Karkur Murr. This increases the number of recorded sites at Eastern Uweinat by almost 40%.

In the evening we had a delightful visitor: a little fox (Rueppel's sand fox, Vulpes rueppeli), that had been prowling around the camp for days. A few days earlier, on a quiet afternoon, it even came in full daylight, happily gobbling up any scraps of leftovers only a few metres from Magdi. This time we piled the leftovers from the dinner (turkey curry) on to a rock about ten metres from the campfire, and the fox showed a distinct affection for indian cuisine, at the same time obediently posing for the flashing cameras. There were some other visitors too: large black desert ants inhabit the valley, and they converge in vast numbers on any food or drink - one morning we found hundreds drowned into the little water that was left in the kettle the previous evening.

Day 10. - Karkur Talh - Unknown Plateau.

Leaving Karkur Talh, we drove north to the large "Unnamed Plateau" to the north-west of Clayton's Craters and Jebels Peter & Paul. Last March we entered it's Main Wadi on the eastern side, and aside a crude engraved cow and a few akacia shrubs, found little of interest. This time we headed for it's jagged western side, where satelite photos indicated a number of bays enclosed by hills. The drive was short and easy, by noon we were inside the largest valley on the western side, surrounded by hills of eroded granite boulders, reminescent of Western Uweinat, just on a much smaller scale.

During the afternoon, we explored all parts of the large valley, but found nothing of interest aside it's desolate beauty. The granite boulders were too small to form meaningful shelters, there was no vegetation whatsoever, and save for a sole decorated potsherd, there was no trace of previous human presence.

Day 11. - Unknown Plateau - Wadi Sora.

As there was clearly little left to explore at the "Unnamed Plateau", we left early in the morning for Wadi Sora on the plain between the plateau and the dune ranges to the west. It was generally good going, with a few soft patches assuring our proper morning exercise. As the plateau's northern end meets the dunes, there was an opportunity to cross a few of the dune ranges, allowing us to take a broad lane that took us all the way to the south of 'three castles', a substantial shortcut.

We reached Wadi Sora by noon. In the afternoon we spent a leisurely time visiting the main caves, and taking walks in the surrounding wadis, visiting the other sites.

Day 12. - Wadi Sora environs.

In the morning, we set out to visit the known sites north of Wadi Sora, then continued to explore the large, 15 km wide bay to the North, jutting in to the western cliffs of the Gilf. Early on we had success, a number of small shelters were discovered with faint paintings, including one of the missing three discovered by Almásy & Rhotert that noone could find up to now.

Continuing our exploration, in a minor wadi we chanced upon a low shelter. Climbing under, we were met with the greatest discovery of the trip. The whole ceiling was covered with paintings of humans, cattle and beautiful polychrome giraffes, all in pristine condition. There are numerous layers, the overpainting sequence clearly visible due to the perfect state of preservation! This is certainly the most significant rock art discovery in the Eastern sahara since the belgian expedition in 1968.

In the afternoon we continued our exploration, the sheer beauty of the landscape compensationg for the lack of any more sites.

Day 13. - Wadi Sora environs.

We continued our exploration of the edge of the cliffs, with it's multitude of wadis and rock islands. Under a shelter unexpectedly we found the horns of an addax, an animal long extinct in the region. Upon a little examination it emerged, that the whole skeleton is there, covered with a matrix of hardened dust and sand. Judging from the condition it must be very old, possibly over a hundred years. (In his book "In air, on sand" Almásy mentions following the tracks of an addax from Peter & Paul to the western cliffs of the Gilf in 1933, then reported seeing the mummified body of probably the same animal in Wadi Abd el Melik a year later.)

We popped in and out of wadis in the maze of rocks, but found nothing more. We finished our search and returned to the wadi north of Wadi Sora to check out a few hidden corners, where we did find two sites with very faint paintings, probably seen by others previously just left unpublished.

Day 14. - Wadi Sora - Aqaba Pass - North-east Gilf.

In the morning, on our way back, we stopped to examine the mysterious brass container at one of the rock pillars near the WWII airfield. Neither Raymond nor Kit recognised it's make or use. Some excitement was caused, when Salama caught a mildly venomous sand snake among the rocks.

Continuing, we drove back to the Aqaba pass, passing the magnificent golden dunes along the way.

The ascent was quick and easy this time. As we drove north, at one point along the north-east side of the 'Gap' we unexpectedly came upon a tiny oasis of several bright green zilla spinosa shrubs growing in a small depression where a dune dammed a wadi runoff. The shrubs were surrounded by a cloud of Painted Lady butterflies (Vanessa cardui), long range migrants that travel all the way to Europe in the summer.

By sunset we rounded the top of the south-eastern half of the Gilf, and made camp among the dunes along the plateau's eastern edge.

Day 15. - North-east Gilf - Hill With Stone Circles - Abu Ballas.

We continued via 'Hill With Stone Circles' and the incredible pink yardangs towards Abu Ballas. At one point along the way both cars neatly got stuck, one after the other, in an invisible patch of liquid sand on an otherwise perfectly firm sand plain, enabling the grinning Salama to finally take his coveted photo of all the group digging and pushing.

This time at Abu Ballas I have managed to take a good look at the "serekh" reported by Giancarlo Negro. I have taken a good look in the best possible lighting, and failed to discern a serekh or any other engraved scene. Possibly the reconstruction was based on special lighting conditions and misleading image enhancement. (We communicated with Giancarlo on the matter, he is in agreement with this finding). I personally believe that the lines themselves could be of natural origin. However there is a very interesting engraving further down the hillside, also found by Giancarlo Negro. It has been suggested that it might represent a falling meteorite, though other interpretations are possible.

Day 16. - Camp - Dakhla - Dunes near Abu Mungar.

Breaking camp, we had a couple of hours' drive till the asphalt road, and shortly we entered Dakhla. After shower, lunch, a quick oil change for the cars, we continued north, making our final camp by the dunes near Bir Abu Mungar.

Day 17. - Abu Mungar - Baharya - Cairo.

We bid farewell to Kit, Raymond and Colonel Ashraf in Baharya. Kit and Raymond continued on an extension of the trip to Siwa, while the rest of us returned to Cairo, making it in to town at nightfall. It was the last evening before Ramadan, with huge crowds, traffic and noise on the streets, harshly jolting us back to 'civilisation'.

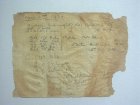

The Uweinat peak documents

The document was found tightly rolled up, with much dust adhering to it, and in a very fragile, damaged condition. It must have fallen out of the bottle as the cairn collapsed at some point, and the neck was broken. As it was exposed, probably it was also soaked several times during the infrequent rainstorms once a decade.

It was evident, that the document consisted of several sheets rolled up together. After delicately brushing off the hardened dust, the roll was treated with steam to enable unrolling without damage. Unrolling revealed, that it was a small booklet held together by a single pin at it's left edge. Fortunately the last page was folded over the front to cover the inscribed first sheet, preserving some parts of the inscription. The paper, despite the water damage and exposure, was well preserved except near the fraying edges, and the sheets could be separated without any difficulty or damage.

The first sheet contained text on both sides, in blue ink. Too much is faded to make the text fully legible, but on the first side there are recognisable italian and english words. On the better preserved rear side, "Marchesi" is clearly recognisable in the first line, confirming the document's already suspected identity. The second sheet contains perfectly preserved inscriptions in pencil, recording three different ascents by Sudan Defence Force parties during 1934. The first, dated 2nd April, confirmed that it was indeed F.G.B. Arkwright and party who left the note in the jar in Bagnold's cairn we found a year earlier. Incredibly, two other parties made the ascent in July and August, giving strong support to the oft quoted line about mad dogs and Englishmen... The remaining four sheets were blank.

There is a short reference to the deposition of this note on the peak in Lodovico di Caporiacco's book, "Nel Coure del Deserto Libico" (p. 101): "... al punto piú alto, che battezzammo Cima Italia, e vi edifiziamo un nostro pilastrino lasciando, in una bottiglia vuota, il 'libro di cima' di Gebél el-Auenát. Noi l'abbiamo inaugurato; chissá chi ne scriverá la seconda pagina e quando ?" [...at a higher point, that we named Peak Italia, we erected a cairn, and left in an empty bottle the 'peak log' of Jebel Uweinat. We have made the first entry; who will write the second page, and when ?]

The existence of english words on the first page possibly indicates that the Italian party copied the Bagnold party's inscription (which is the only one missing from the sequecce of notes left by ascents till today, probably the Italian party took it), however the ink is too faded to read the full text. When I have some time, an attempt will be made to transcribe as much as possible using UV and IR light, and various image engancing techniques.

See also Bernhard's website with photos of our trip at:

www.gilf-kebir.de

and Kit's trip diary on his website at:

www.kitmax.com

An article describing the most important rock art discoveries during this trip was published in Sahara 14