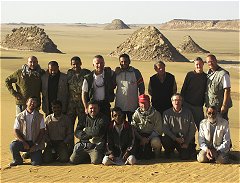

Click on image for list of participants

|

Great Sand Sea - Gilf Kebir Expedition

13th February - 2nd March, 2003

NOTICE: The rock art photos on this page are strictly copyrighted ! No photo may be copied / used for any purpose without written permission.

|

Two years of routine preparations and hassle free trips gave a false sense of confidence, but just before the trip we received the jolting reminder that traveling to the remote parts of Egypt is still very much up to the whimsy of the high authorities. Early February, just a week before we were due to start, the military authorities came up with a new rule that all groups wishing to travel to restricted areas must pay 200 dollars per day for the escorting military officer, irrespective of group size. This pretty much closes the desert for individual travel, and puts a heavy burden on the few specialised local operators who try to make a living out of organising desert expeditions. After some negotiations we were able to reduce this charge to half with the argument that our permits were received well before the rule came into force, but still it was a painful additional expense, especially knowing that it was extorted for something totally unnecessary. I can only hope that by the time our next Gilf expedition is planned for 2004, the authorities come to their senses...

Day 1. - Cairo - Siwa.

After the dull drive from Cairo, we were in Baharya by mid morning. Our departure coincided with Eid al-Adha, and the permits for the cars and the drivers were to be given at Baharya, together with the escorting officer. Not surprisingly things were rather slow due to the Feast, it took several hours to complete the paperwork and locate Captain Ashraf. We were planning to make Siwa by the evening, and the precious daylight hours were ticking by, untill finally we were ready to leave after 2pm. The road between Baharya and Siwa is in a dismal state, in many places the roadside tracks offer a better going than the almost non-existant tarmac. To make matters worse, there are about a dozen checkpoints along the 400 km stretch, each taking 5-10 minutes to pass. At the first, we were almost ordered back to Baharya on some technicality with the permits, it took captain Ashraf a lengthy negotiating session to arrange the matter to be sorted out in Siwa. With all these delays, we reached Siwa around 11pm, spending the night in a rather nondescript local hotel.

Day 2. - Siwa - Camp 1 in Great Sand Sea.

The morning was spent fueling the cars and buying some last minute supplies, while Ashraf and Khaled sorted out whatever it was with the permits. Apparently it was no big issue, as the matter was settled in ten minutes. By noon we were all set to go, started out towards Bir Waheed a short distance south of Siwa. There is a built track till the small oasis offering a relatively easy way out of the Siwa depression, bordered on the south by steep slopes of sand.

We had some apprehension taking the heavily loaden cars up the long sand slopes, then in among the dunes. Each car carried over 700 litres of diesel, plus another 800-1000 kgs of passengers, water and supplies. We let the tire pressures well down, and started out south. In retrospect, the track proved the most difficult. In places the sand was very soft from the many passing vehicles, and the heavy cars became bogged several times. However as soon as we passed Bir Waheed, the going became firm along the interdune corridors. We made our first camp about sixty kilometres south of Siwa, among the last tufts of remaining vegetation.

Day 3. - Camp 1 - Camp 2 in Great Sand Sea.

Our aim was to cross the Great Sand Sea along the shortest route, aiming for the large expanse of open flat serir at the western edge, jutting a little into Egyptian territory. This route was pioneered by the Long Range Desert Group, we found several of their discarded petrol tins along the way.

Immediately to the South of Siwa the great dune ranges are not as organised as further south. It's a great mass of rolling, jumbled sand, with many rock outcrops and firm ground in between. Beyond our first camp, the corridors filled with sand, and the dunes became the familiar long, impassable parallel ranges. The dunes forced us towards the south-east, but every now-and-then a gap between the great ranges offered a jump to the west, setting us back on course. All the day was spent zigzagging among the dunes, occasionally having to push a stuck car (usually the third, heaviest) out. However no recovery took more than 10-15 minutes at most, it was a surprisingly fast, easy going. By the evening we have covered most of the 150 kilometre distance, and made camp along the last large dunes. Just before camp, we had an unusual incident, showing how the sand texture can change over very short distances. Without any warning the lead car slowed and tilted sharply to the side. As we climbed out, it became clear that on one side the wheels were on firm sand, while the other side sank to the running boards into a patch of very soft sand (the car got out with one push).

Day 4. - Camp 2 in Great Sand Sea - Silica Glass Camp.

Beyond our camp, the nature of the sand changed dramatically. We were still some 60 kms from the edge, but the large crested dunes disappeared, and the country became a rolling sea of low firm dunes, offering a fast, easy passage. In less than an hour we reached the gravel plain. The geologists in the team set out for a meteorite hunt on the flat, featureless expanse, but we had no luck. We continued towards Clayton's Big Cairn, and a short distance beyond found a Long Range Desert Group fuel dump.

From Big Cairn, we skirted the western edge of the Great Sand Sea, dipping slightly into Libyan territory to round the westernmost dune range. The going was firm and fast all the way, we covered 200 kilometres in less than three hours. We made camp at the tip of the dune range flanking the westernmost Silica Glass corridor.

Day 5. - Silica Glass Area.

One of the main objectives of the geologists in the party was to extend the sampling of the Silica Glass area started on several previous trips to the 'Lost Corridor', an interdune corridor blocked from all sides by a series of very soft transverse dunes. With a single car we tackled the difficult part, and made two sampling areas with good results.

Day 6. - Exploring the 'Zarzura' plateau.

The east-west running Wadi Gubba is considered to be the northern edge of the Gilf Kebir. However geologically the Gilf continues northwards for another 100 kilometres in the form of a low, 30-50 metre high plateau that gradually reduces into the flat serir to the north. This low plateau contains three parallel valleys, and on previous trips Giancarlo found vegetation and traces of prehistoric habitation in the eastern two. While the three geologists, Vincenzo, Romano and Benito stayed at the Silica Glass base camp to continue their work, the rest of the party left with two cars to explore the largely unknown plateau to the west. Some features of the plateau and the valleys fit the description of the 'Zarzura' valleys as recorded by Almásy from the Kufra natives. We started our exploration in the easternmost valley, where some years ago Giancarlo and party located a large dry guelta at the head of one side branch, and some stone circles on the plateau above.

We walked into several side wadis, but aside the known stone circles, found no traces of prehistoric habitation or rock art, except a single tethering stone and a nearby millstone. Tethering stones are common in the central and western Sahara, but it is the first clear example I have seen in the Gilf-Uweinat area (however Giancarlo did find many previously at other localities in the area).

The most interesting discovery of the day was a strange plant along the side of a side wadi. What appeared to be a pile of discarded ropes from afar turned out to be a jumbled mass of twisted vines with sparse little bright green leaves growing only in sheltered, shady spots. The plant was later identified as Cocculus pendulus, a shrub common in the Eastern Desert and the Sahel zone, but this is the only known example in the Libyan Desert.

Day 7. - Exploring the 'Zarzura' plateau.

In the morning we set out to the unexplored westernmost of the three valleys. It was a rough drive along the plateau top to the second valley, where we had some pushing to do in the soft sand of the wadi bed.

We ascended the plateau top once again, and reached the third valley by midday. We drove up it's length for about ten kilometres. Vegetation was limited to intermittent low shrubs and grass, we have seen no trace of acacias or any prehistoric or recent human habitation. A little disappointed, we retraced our tracks along the bumpy plateau top, reaching Silica Glass base camp by sunset.

Day 8. - Silica Glass Area - Western Gilf Kebir.

In the morning we drove down to the southern tip of the Silica Glass area to visit lake Jux, a prehistoric lake that formed in a depression among the dunes. The lake filled and dried out several times, leaving a series of mud layers intermingled with thousands of stone tools.

Late morning we started on the long way south to Wadi Sora, rounding the western side of the Gilf Kebir. We crossed Wadi Gubba and the broad mouth of Wadi Abd el Melik, and entered the jagged, broken foothills of the Gilf. At first, aided by Landsat images, we found easy going in the flat sandy bottom of wadis among the outliers. In a short wadi we found some live and many dead akacias, a welcome chance to replenish our dwindling firewood.

Eventually the cliffs became a solid wall that forced us several kilometres to the west, into Libya. The plain at the foot of the cliffs is full of rocks and small watercourses, offering a rather slow and difficult going. Soon we hit a well used track that apparently made a much larger loop to the west than we did. Evidently despite the official ban many people take this shortcut to Wadi Sora accross the Libyan border (including the clearly recognisable tracks of the huge trucks of the Egyptian border patrols). Due to the slow speed, we were unable to reach Wadi Sora by the evening as planned, we camped some 70 kilometres to the north.

Day 9. - Camp at Western Gilf - Wadi Sora.

In the morning it was a torturous two and a half hours to reach Wadi Sora on really bad, rocky terrain. Furtunately the cars were substantially lighter by now, but still we looked often at the springs with concern. Fortunately save for a cracked middle leaf in the front on one car, nothing serious happened, the cars took the beating well. Base camp was made at the dune in Wadi Sora, from where we intended to spend three days exploring the surroundings, eliminating the remaining blank spots. First afternoon was spent visiting known sites, including the ones discovered last October. A re-examination of the area finally revealed the 'lost' site F of Rhotert, inside a little rock crevice in a shelter which was surveyed repeatedly by both myself and others in previous parties, apparently not very thoroughly. On the floor of the shelter I found a little cylindrical metal cannister - one of the film cannisters of Rhotert, discarded seventy years ago.

On the way back to Wadi Sora we discovered a new site with faint red paintings of giraffes and humans.

Day 10. - Exploring wadi in Gilf north of Wadi Sora.

Immediately north of the Wadi Sora bay, Landsat images reveal a large broad wadi running parellel to the western edge of the Gilf, having it's mouth some 40 kilometres to the North of Wadi Sora. There are no reports of any previous exploration, we planned to spend the day surveying the valley, hopefully finding new rock art sites. We retraced our tracks of the previous morning with much lightened two cars till we were level with the wadi mouth on the plain, then made a direct traverse on the rock filled talus slopes towards the wadi. We left one car at the wadi mouth and set out to explore the interior.

The wadi wound south, slowly rising, until coming abrubtly to a halt at the northern cliffs of the large bay at Wadi Sora. Climbing to the rock edge, we had a breathtaking view, no more than ten kilometres from our camp. From this vantage point it became apparent how much we went uphill over the 20 kilometres. The wadi mouth is level with the plain, yet we were sitting at least 250-300 metres higher, on the top of a near-vertical cliff.

The wadi history was clear. At some time it was a major watercourse like the other valleys further east, to which it much resembles in dimensions and direction. However as the western cliffs eroded, the headwaters became cut off, and it turned into a dry, hanging valley where the only further erosion was the slow crumbling of the cliffs. It must have been as dry as present in prehistoric times, we found no signs of habitation or rock art, and only a few meagre tufts of vegetation. Near the cliff edge, rocks showed some bizarre wind erosion features, much like the vestibule of a building designed by Gaudi.

In the afternoon we returned to Mushroom Rock and the surrounding area, where Giancarlo and Aldo Boccazzi found a small shelter with engravings 15 years ago. It's a beautiful area, with reddish sand dunes mingled with huge, smooth walled white hills, remnants of the eroded plateau.

We were fortunate enough to locate a new rock art site in a large shelter in the side of one of the hills - faint engravings of giraffes, and some paintings of humans in the wadi sora style on the rear wall.

The remainder of the afternoon was spent with a thorough survey of the area. The lack of further rock art sites was compensated by a fabulous landscape.

Day 11. - Exploring area north of Wadi Sora.

The day was spent exploring the broken foothills of the Gilf to the north of Wadi Sora, between the place where we left off the survey last October, and the Mushroom Rock area further north. The area is full of low hills much resembling the large valley immediately to the north of Wadi Sora, with many shelters providing good opportunity for paintings, yet we found nothing in the whole area.

The biggest excitement occurred when the sharp eye of Salama spotted a barely visible agama on a rock some ten metres from the moving car - an amazing feat ! The agama posed obediently for the snapshots, it actually had to be nudged to make a dash for the crevice called home.

On our way back to Wadi Sora, we passed by Chianti Camp. The precious relics were still there intact, however to our amazement the walls were filled with charcoal grafittos made in August and September 2002 by an obviously large group of Ethiopian, Eritrean and Somalian refugees. Apparently this remote route is used in the summer by Libyan people smugglers who take refugees to Benghazi, then probably on to Italy and the rest of Europe...

In the evening at Wadi Sora I spent a couple of hours studying the large cave in the light of a white LED torch, which revealed some surprising, never before seen details. Very faint, small human figures in yellow and white came to light, which are totally invisible in the yellow reflected light illuminating the shelter during the day. The figures are no more than 3-5 cms, and appear to belong to the earliest phases of the paintings. This special lighting revealed other details like the little red and white figures which are visible, but unidentifiable in daylight.

Day 12. - Wadi Sora - Karkur Talh.

In the morning we passed by the large rock island south of Wadi Sora on the plain near the WWII airfield, where Stefano Laberio-Minozzi found some engraved giraffes some years before. This time we located the engravings, high in an enlarged crevice in the middle of the rock.

We continued south along the easiest track, briefly stopping for lunch at Claytons Craters. We reached our camping spot in the south branch of Karkur Talh by mid-afternoon, allowing a leisurely visit to the numerous rock art sites in the vicinity of the camp, including the big shelter with paintings discovered by Almásy and Rhotert in 1933.

Day 13. - Ascent to the "White Spot".

The mysterious "white blob" so prominent on Landsat photos at the western edge of the Hassanein plateau was intriguing me ever since I first saw it on high resolution images. In October 2002 we planned to make a visit, but the unexpected deep canyon on the far side of the plateau, separating it from the main mass of Jebel Uweinat, allowed only a distant peek that revealed nothing.

While the majority of the group stayed in Karkur Talh to visit the numerous rock art sites, a small party consisting of Mario, Vincenzo, Salama and András set out at dawn in the unexplored south western branch of Karkur Talh, towards the vertical cliff face where we hoped an ascent could be found.

We trudged along the wadi bottom for several hours, scrutinizing every shelter and crevice along the banks, but much like the other valleys, there was a long stretch of several kilometres totally devoid of any rock art. Then all of a sudden, near the convergence of several lateral wadis, we came upon a large shelter containing lovely, well preserved paintings. The less preserved right side contains small human figures and giraffes, over some faint older 'roundhead' style figures. The right panel has well preserved paintings of the bovidian period, including some unique, thread-like human figures never seen elsewhere.

As we continued, in rapid succession we found another five major shelters and a number of smaller ones, all containing paintings from the bovidian period. We found a unique scene showing a dog on leash, and an exceptionally large, elaborately decorated cow measuring about 70 centimetres accross, about four times the usual size.

Slightly further upstream, under a large boulder, Salama discovered very faint paintings on the low and dim ceiling. On location it was impossible to discern anything, but the flash of the camera revealed a series of unique paintings from the 'roundhead' period, including a lovely giraffe, and a strange squatting figure with one set of legs and two bodies. Unfortunately the state of preservation is bad, but the depicted scenes make this one of the most important early rock art sites at Uweinat.

Beyond this point the wadi became very rocky, and the steep talus slopes offered a relatively easier way. We climbed ever higher on the slope, approaching the spot in the cliffs where the deep shadows hinted that there may be a canyon entering the cliffs, where hopefully we could find a way up to the plateau top. We have spent much time photographing the newly found rock art sites, and we only had two hours of daylight left. Vincenzo, who had difficulty keeping up with the rest on the steep slope, very unselfishly offered to make camp in a sheltered sandy spot, allowing the three of us to complete the steep climb before sunset. Leaving some of our water behind with Vincenzo, we made good progress, and soon stood at the foot of the cliffs where a narrow boulder filled canyon was revealed. After some scrambling on the boulders we spotted a rocky slope that looked an easy way up, and a little more than an hour after parting, we stood at the rim of a huge flat sand filled amphiteatre, surrounded on all sides by jagged rocks - the mysterious white spot !

The low dark dome in the middle of the crater (also visible on satelite photos) instantly explained the hitherto mysterious origin. Closer scrutiny confirmed the initial assumption that it was indeed basalt. The depression formed (as Vincenzo later explained) by the rising basalt dyke fracturing the surrounding sandstone in a radial pattern, enabling a much faster erosion by wind and water than the surrounding rock. The 'crater' is an erosion feature, not a volcanic crater in the true sense. The fact that it seems to be perched on the edge of the vertical cliffs of the plateau is mere coincidence, the cliff erosion has not breached the crater walls yet.

We had enough sunlight left to make a quick traverse, take a couple of photos, and yell down to Vincenzo some 500 metres below us, just visible with binoculars. He could not see us, but heared the call, and we could just barely pick out his faint response.

We made camp at the far end of the circular depression, in a small valley beyond the single live acacia. Salama prepared the lovely bedouin bread for supper, then we packed ourselves into our sleeping bags in anticipation of a very cold night.

Day 14. - Descent from the "White Spot".

It proved to be colder then our worst expectations. There was a chilly wind throughout the night, and by 5am both me and Salama were up shivering around the small fire in two degrees. As dawn approached, the temperature dropped even more. As I climbed to the crater rim to make the sunrise photos, I measured just about zero degrees, my numb hands could hardly manage the camera controls. There was a clear condensation with every breath. However the view was absolutely marvelous, with the rising sun hitting the face of the towering 'Three Graces' on the south side of the mountain.

We promised Vincenzo to be down by 10am, so we had only a few hours to explore. We entered the narrow valley to the east of the crater, which was a beautiful spot of eroded sandstone columns and golden sand. It reminded me very much of the top of the Tassili N'Ajjer plateau in Algeria. Only the rock art sites were missing...

The missing feeling did not last long. Soon we came upon a low shelter, in which the clear shapes of cattle were discernible from a long distance - people were living up here too, where they must have scrambled up on the same boulders in the steep canyon as we did. There was another shelter a hundred metres from the first. Both contained shelter scenes of the typical Uweinat bovidian period style.

Based on the satelite photos, the top of the Hassanein plateau has several similar sand filled eroded valleys, there may well be many more sites. Fortunately there is a good excuse to go back and explore some more! This time we had to return, pausing for a panorama of the white spot from the top of the eastern rim.

On our return we took some samples from the central basalt dome. On the floor of the crater we found several undecorated neolithic potsherds.

The descent was quick on the known route, in less then an hour we were reunited with Vincenzo, who had a much more comfortable night in his sheltered cove than we did up in the crater. We continued our descent, and by midday we reached the rock art sites of the day before. Searching along the far side of the valley that we left unexplored, we came upon an extraordinary shelter filled with a multitude of perfectly preserved paintings.

A short distance further, we found a small shelter filled with well preserved tiny human figures.

After lengthy photo sessions, we continued exploring a number of lateral wadis, without any further results. We reached the car waiting for us by at the beginning of the broad main valley of Karkur Talh by mid-afternoon.

Day 15. - Karkur Talh - Camp along eastern Gilf Kebir.

In the morning we spent a little time exploring a western side wadi near the entrance, and was surprised to find a large number of scattered belongings of nomads, apparently left behind in a big hurry. Some dates on the found tins were from the early fifties, indicating that Tibou nomads have returned to Uweinat after the War.

The remainder of the day was spent starting our return journey, driving up to the southern tip of the Gilf, then skirting the plateau to the east. We made camp at a spot 60 kilometres south of 'Hill with Stone Circles on Top'.

s

Day 16. - Hill With Stone Circles - Camp beyond Abu Ballas.

Continuing our return journey, we stopped at the fantastic pink yardangs at 'Hill with Stone Circles on Top'.

We made a detour to visit an ancient ochre mine discovered by Giancarlo and Vincenzo on an earlier trip. The red ochre beds have clearly been mined, yet curiously no object of human origin was found anywhere near the workings. At some disctence from the mine, we have discovered a large epi-paleolithic or neolithic habitation site, the latest sign of human presence in the area. The evidence seems to suggest that the beds were worked in neolithic times by the same people who used red ochre for the paintings in the Gilf and Uweinat.

On our way towards Abu Ballas, we passed another ancient lakebed with well shaped yardangs.

After visiting Abu Ballas, we continued for another hundred kilometres towards the road, making camp at the foot of the scarp running parallel to the track.

Day 17. - Camp beyond Abu Ballas - White Desert.

In the morning we made our last group photo on the dune behind the camp, then started back to civilisation.

We reached Dakhla by late morning. Some of the group wished to take a speedier minibus to Cairo to visit some of the sights before the flight, and Ashraf was glad to join, getting home to Baharya a day earlier. After changing oil in Dakhla, the remainder of us took a leisurely drive north, hoping to camp at the dunes before Abu Mungar. However, like on almost every spring trip previously, weather intervened. A strong south wind started in the afternoon, and by the time we reached the dunes it was a true sandstorm. We decided to continue to the White Desert a further 100 kms north, where we could expect some more shelter. Incredibly by the time we made camp the wind died almost completely, and we had a very pleasant peaceful last night among the white domes.

Day 18. - White Desert - Cairo.

After packing up the supply boxes, we made the long drive to Cairo with just some brief stops, reaching the bustling city by mid-afternoon.