|

The Tassili N'Ajjer |

|

|

The plateau or 'tassili' of N'Ajjer rises to approximately 5-600 metres above the plain of Djanet, and there is no access to the top with vehicles. Two very steep passes can only be tackled on foot and by pack donkeys. Thirty kilometres to the north, there is a pass suitable for camels (Akba Assakao), but is rarely used. All of the top of the plateau in the vicinity of Djanet, encompassing most of the important rock art sites and probably the most fascinating landscape in the Sahara, lies within the Parc National du Tassili. This does not imply any facilities within the park, but it does justify an entrance fee (plus extra for a 'photography permit'), and it is not allowed to enter the area without an 'official guide'. As it is not possible to drive onto the plateau, and maps are of no use in the maze of rocks, not to mention finding the rock art sites, a guide is necessary anyway. All of the travel agencies in Djanet survive by organising treks to the plateau, so once there it is possible to arrange for a tour starting the next day, complete with guide plus pack animals and their herders to carry the luggage, food and water. The best time to go is mid-autumn, or mid-spring. The plateau is quite high, so it's noticeably cooler than on the plain. In the winter months it can go below zero during the night (Lhote mentioned water in the basins freezing, and even some light snow !), and even in the daytime it can stay uncomfortably cold. From May to September the daylight temperatures will go above forty despite the altitude. In October and April it will be a pleasant 25-30 degrees during the day, and night temperatures will not drop below 10 degrees. |

|

Organising Tours |

|

|

Two kind of tours are available: "full service", when the agency provides for tents and food (usually a variation on the cous-cous and rice theme), and the "no frills", when the above are excluded. The second is the better choice if You turn up in Djanet, as the cost for full service is usually double, and for a fraction of the cost difference it is possible to bring along a much more varied menu. Bulk and weight is not a problem, as the pack animals carry the load. Typically a tour on the plateau will last between four days and a week, subject to Your appetite for prehistoric paintings and Your budget. Depending on agency and Your bargaining abilities, (as well as the number of people), daily fees will be from $20 per person for a larger group to $40 with only two people no frills, double that if food and camping gear included (about $160 a day if booked with a European agency, including flights). |

|

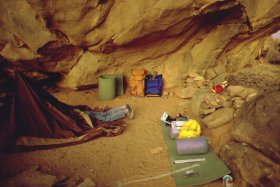

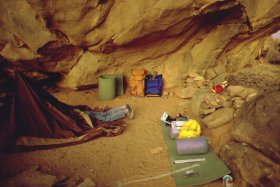

There are designated camping areas on the plateau, no different from any other spot but ensuring that camper's litter stays localised. In some places previous travellers have built stone windbreaks, which can be handy on windier nights. There are thrash areas with piled up stone walls, use these as opposed to burying opened cans and other litter in the sand - this can cause nasty surprises to someone camping there later. |

|

Possible Itineraries |

|

|

4 days Akba Tafilalet - (Antelopes) - Tamrit - Tan Zumaitak - Tamrit Tamrit - In Itinen - Sefar Sefar - Tamrit Tamrit - Timenzouzine - Akba Tafilalet 5 days Akba Tafilalet - (Antelopes) - Tamrit - Tan Zumaitak - Tamrit Tamrit - In Itinen - Tin Aboteka Tin Aboteka - Tin Tazarift - Sefar Sefar - Tamrit Tamrit - Timenzouzine - Akba Tafilalet 7 days Akba Tafilalet - (Antelopes) - Tamrit - Tan Zumaitak - Tamrit Tamrit - In Itinen - Tin Aboteka Tin Aboteka - Tin Tazarift - Sefar Sefar Sefar - Jabbaren Jabbaren - Aouenghet - Jabbaren Jabbaren - Akba Arum The main sites described will give an almost complete coverage of the Tassili rock art. For those wishing to have the full picture, it is also possible to visit several smaller sites lying outside the normal 'tourist circuit', one can count on doing 20-25 kilometres a day at a reasonably comfortable pace. If You know the particular sites to visit, the guides will show the way (and the rock art sites), but they are unlikely to make suggestions other than the known sites. |

|

The daily routine |

|

At sunrise you break camp and load the animals, which disappear with the herders on the most direct route to the next campsite. The guide takes a more leisurely place, visiting interesting sites along the route, usually catching up with the animals by early afternoon. |

|

You'll need a small rucksack to carry the daily necessities (water, something to nibble, warm clothes, camera, etc.). As the plateau is at an altitude of 1200-1400 metres, it can be bitterly cold in the morning from late autumn to mid spring, and can remain so all day if there is a thin haze or cloud cover. You're faced with the choice of packing away warm gear in the morning, and shivering until the sun makes its presence felt, or having to carry all till the afternoon. It's a matter of trial and error; You get the feel of it after the first day up the plateau. |

|

Health & Dangers

|

|

The deep desert is one of the healthiest places on earth,

due to the almost sterile air and surroundings, there are very few

risks & dangers. Other than accidents, which can happen

anywhere (and can be avoided with common sense), the only dangers lurking in the desert are snakes

(especially the horned viper), and scorpions. The former are deadly, but are rare and easily avoidable. They leave distinct tracks in the sand, do not actively seek humans, and typically stay dormant in the cooler autumn to spring months. In all my Saharan travels I have only encountered tracks, no live animals. Still, it is common sense not to walk into any area with thick undergrowth where you cannot see where you put your feet, and camp at a distance from vegetation. |

|

Scorpions are more common, but less deadly. Though they tend to

shy humans, occasionally they crawl under tents or into one's

shoes outside, so it's wise to shake one's shoes in the morning

before putting them on. Otherwise it's just a matter of avoiding

to put one's hand into hollows and crevasses in rocks (why people

still do it beats me ?!). |

|

Photographing Rock Art |

|

|

Getting good pictures of your favourite sites can be a rather frustrating activity. The engravings are either situated on boulders on the ground, or up on cliff faces, and its only rarely possible to have them at the right distance and the right perspective. Should this actually happen, the lighting usually makes the faint engravings practically invisible. The perspective problem arises from not being able to go away enough along a perpendicular axis from large engravings, either if flat on the ground, or high on a cliff. The first one can be solved by having a non-distorting ultra wide angle lens (24 or 20 mm), while the second by taking the photo from the valley with a long telephoto lens (200 - 300 mm usually suffices). The lighting is more difficult. Ideally one needs to wait for the sun to come into the proper position for the light to strike almost at a right angle to highlight the engraving, but this may take more time than is available (except if getting photographs IS the primary purpose of the trip), and will not work at all with a curved surface. Some engravings will remain permanently in the shade, or be only half illuminated, with the contrast too big for the film to manage. For engravings in full sunlight a remotely positioned high power flash will usually give the proper side lighting, but it will add considerable bulk, and an extra tripod is needed (or a helper). For the ones in the shade, a small flash will do, but it also has to be from the side, possibly aided by another on the camera (the side light needs to be at least twice as intense as the one on the camera). If no flash is available, a makeshift mirror made from aluminium foil on a flat board can do wonders, but the illuminated area is only the size of the mirror, so its unsuitable for larger pictures. The paintings are usually much smaller than engravings, thus the perspective problem does not arise (though an ultra wide angle may help in shelters with low ceilings to get the whole scene). The direction of the light fortunately does not matter. However paintings are invariably found in rock shelters that rarely or never get direct sunlight (one of the factors helping preservation). The best is to use a tripod, which eliminates the problem, or a suitably high speed film (over 200 ASA), but this will compromise quality somewhat, and the same film will not be suitable for full sunlight pictures, so two cameras will be needed. Flash should not be used as it may damage the paintings due to the UV component (this is not proven, nevertheless the use of flash is not permitted by the guides on the Tassili). The mirror trick is more difficult, unless there is some sunlight reaching at least the floor of the shelter, but then the reflected light is usually enough by itself. With a little effort however, surprisingly good results can be obtained with two mirrors, one fixed outside the shelter in direct sunlight, the other directing the reflected light up to the pictures on the roof. There is a technique which has been used by many early explorers (including the Lhote team in the Tassili) to make the paintings brighter and more photographable - wetting with a sponge. True, this removes surface dust, and makes colours more vivid, but the technique invariably fades the painting after a few attempts, and the moisture may loosen the rock itself, causing bits to fall away. Unfortunately many of the most beautiful of the Tassili paintings have been lost this way, and the ones in the Akakus in in Libya are also much damaged. PLEASE, DO NOT WET THE PAINTINGS UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCE. Having one good picture is not worth becoming an accomplice to their destruction. |

|

|

|